Diagnosis

A provider guide to diagnosis of alpha-gal syndrome (AGS)

ICD code

Key publications

Diagnosis & management

Commins

Diagnosis & management

Platts-Mills, et al

Clinical history

Alpha-gal IgE

Alpha-gal IgE

test codes

Total IgE

Additional

blood tests

Less recommended

blood tests

The WRONG test

Skin

tests

Seronegative cases

Other mammalian

meat allergies

The GI phenotype

of AGS–COMING SOON!

The final element of diagnosis depends on how they respond clinically to a diet avoiding red meat.17

ICD code

ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code

Z91.014

Allergy to mammalian meats

Key publications

There are two excellent papers on diagnosing and managing alpha-gal syndrome, written by leading experts. In addition, there is a paper comparing AGS and other forms of mammalian meat allergy and a clinical update on the GI phenotype of alpha-gal syndrome from the American Gastroenterological Association.

If you have more than a casual interest in alpha-gal syndrome, you will want to read all four of these papers. Although this page draws heavily from these publications, it is not a substitute for them.

Key papers on the diagnosis and management of alpha-gal syndrome

- Commins SP. Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients. Expert Review of Clinical Immunology. 2020 Jul 9:1-1.

- Platts-Mills TA, Li RC, Keshavarz B, Smith AR, Wilson JM. Diagnosis and management of patients with the α-Gal syndrome. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2020 Jan 1;8(1):15-23.

Key papers comparing AGS and other mammalian meat allergies (includes UptoDate)

- Wilson JM, Platts-Mills TA. Red meat allergy in children and adults. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2019 Jun 1;19(3):229-35.

- Allergy to meats. Commins SP. In: UpToDate, Feldwig, AM (Ed.), UpToDate, Waltham, MA. (online). Updated: Jan 28, 2020. Literature review current through: Oct 2021.

- See Forms of Red Meat Allergy for more information.

Key paper on the GI phenotype of AGS

- McGill SK, Hashash JG, Platts-Mills TA. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Alpha-Gal Syndrome for the GI Clinician: Commentary. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online February 25, 2023. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2022.12.035

- See AGS and Gastroenterology for more information–coming soon!

Highlights from

Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients

Scott Commins, MD, PhD

January, 2020

The following are extracts taken directly from this paper:

Highlights

- “Alpha-gal Syndrome (AGS) is an IgE-mediated allergy affecting an increasing number of patients worldwide

- AGS is characterized by delayed reactions after eating non-primate mammalian meat (e.g. beef, pork, lamb) or foods, medications, and personal products that contain mammal-derived ingredients

- AGS can be a challenging clinical diagnosis to make due to delayed reactions and guidance is provided for practicing clinicians to assist with recognizing and managing these patients

- Unique among food allergies, AGS is due to a carbohydrate-directed IgE response, can occur at any age, and appears to arise following a tick bite

- Patients often present with nighttime urticaria, angioedema, anaphylaxis, or even isolated gastrointestinal symptoms that are highly influenced by co-factors, including exercise & alcohol

- Owing to numerous ‘hidden’ alpha-gal exposures beyond red meats and the need for individualized guidance, we recommend co-management with dietician colleagues”18

Characteristics occur in 85% of patients with AGS

- “Onset in adult life after eating mammalian meat without problems for many years

- Reactions range from pruritus, localized hives or angioedema to anaphylaxis

- Patients can report strictly gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhea, abdominal cramping, emesis) almost to the exclusion of cutaneous, cardiovascular or respiratory manifestations

- Reactions start 3-8 hours after eating non-primate mammalian meat (or consumption of dairy, gelatin, or other mammalian-derived products)

- Positive testing for alpha-gal IgE (>0.1 IU/mL)

- Improvement of symptoms when adhering to an appropriate avoidance diet

- Description of large local reactions to tick or other arthropod bites, often including report of an ‘index’ bite that behaved differently than prior bites”18

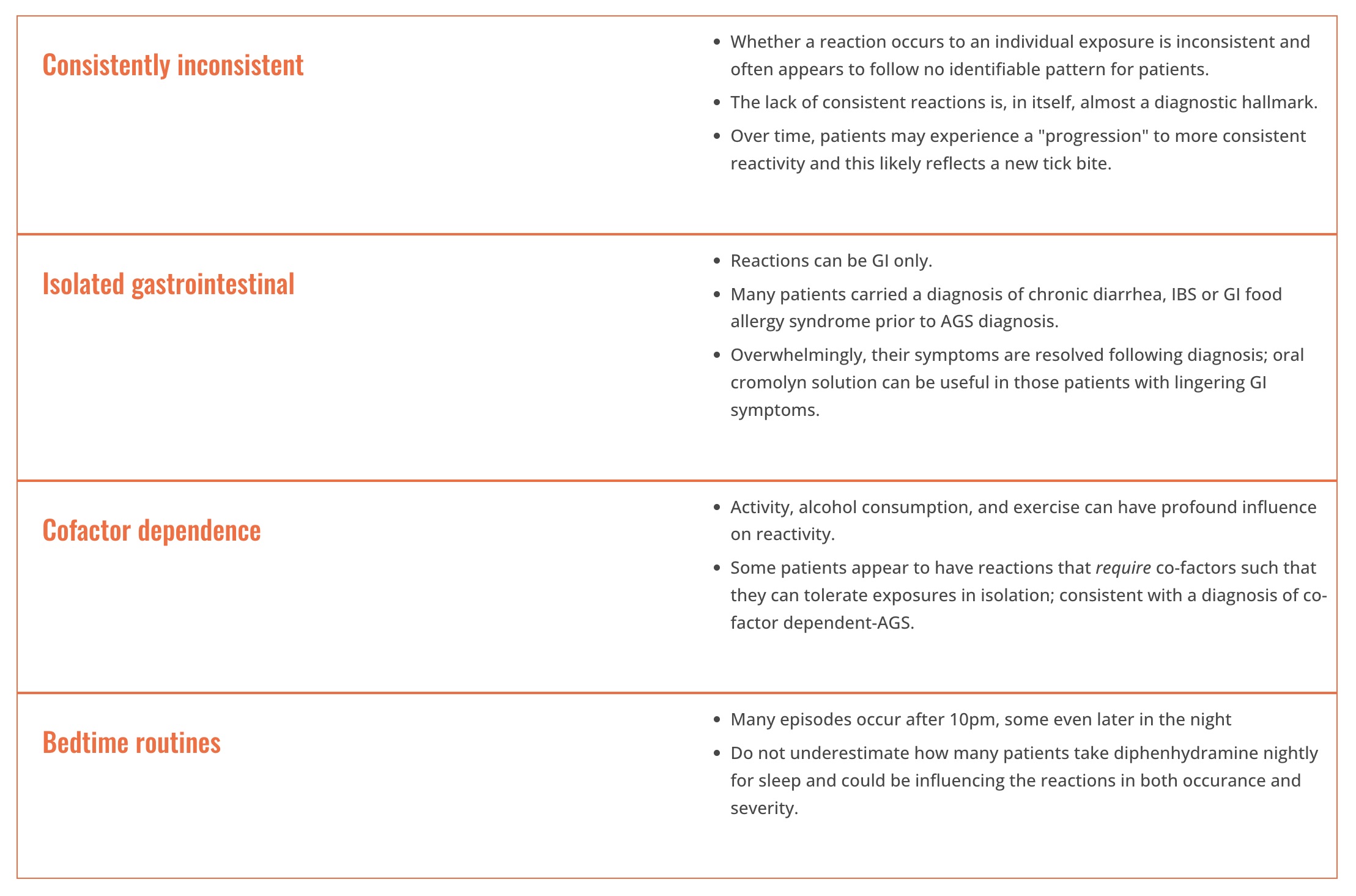

Clinical pearls for diagnosis and management of patients with AGS

adapted from Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients by Scott Commins, MD, PhD18

Highlights from

Diagnosis and management of patients with the α-Gal syndrome

TAE Platts-Mills, MD, PhD; RC Li, DO, PhD; B Keshavarz, PhD; AR Smith, MD; JM Wilson, MD, PhD

September, 2019

The following are extracts taken directly from this paper:

Classical cases

- “They have onset in adult life after eating meat without problems for many years.

- Reactions range from localized hives or angioedema to severe anaphylaxis, which requires emergency treatment and admission to hospital.

- Reactions start 2 to 6 hours after subjects have eaten meat of mammalian origin, and the severity of reactions is not predicted by the delay.

- They have positive sIgE for a-Gal. If the antibodies are greater than or equal to 2 IU/mL or more than 2% of the total IgE, this makes the diagnosis very likely. We often measure total IgE because some cases are nonatopic and have low total IgE. Recently, we saw a case with a convincing history whose total serum IgE was 6.0 IU/mL and sIgE to a-Gal was 0.8 IU/mL. Thus, although the sIgE was less than 1.0 IU/mL, it was nonetheless more than 10% of the total IgE.

- The final element of diagnosis depends on how they respond clinically to a diet avoiding red meat.”

From conversations with allergists working in areas with a large number of cases it appears that at least 80% of cases fit the classical description, where both diagnosis and primary treatment are relatively straightforward. However, it is important to realize that many cases do not present classically.”17

Nonclassical cases

Pediatric cases

“There are a significant number of pediatric cases and the published data suggest that the condition in children has similar features. In particular, the specificity and titer of sIgE, the delay between eating meat and reactions, the relationship to tick bites, and the response to diet are all similar.”

Rapid onset symptoms

“Most evidence is consistent with a delay of 2 to 6 hours; however, a recent study found that 16% of subjects with the syndrome reported subjective symptom onset in less than 2 hours. Moreover, faster reactions were reported in a recent cohort from South Africa, and have been consistently observed with pork kidney, both in clinical practice and in challenge tests.”

Gastrointestinal

“In our practice the most important group of nonclassical symptoms is those that involve the gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointestinal elements are not uncommon as part of reactions that include hives. However, there are patients who have episodes of abdominal pain without any skin involvement. Those cases are a problem because the possibility of food allergy is not obvious, and they can be severe. Indeed, 2 of the most severe cases we are aware of manifested with significant gastrointestinal symptoms but little if any dermatologic involvement.”

Arthritis and pruritus

“Other diagnoses that arise less commonly are arthritis and chronic pruritus.”17

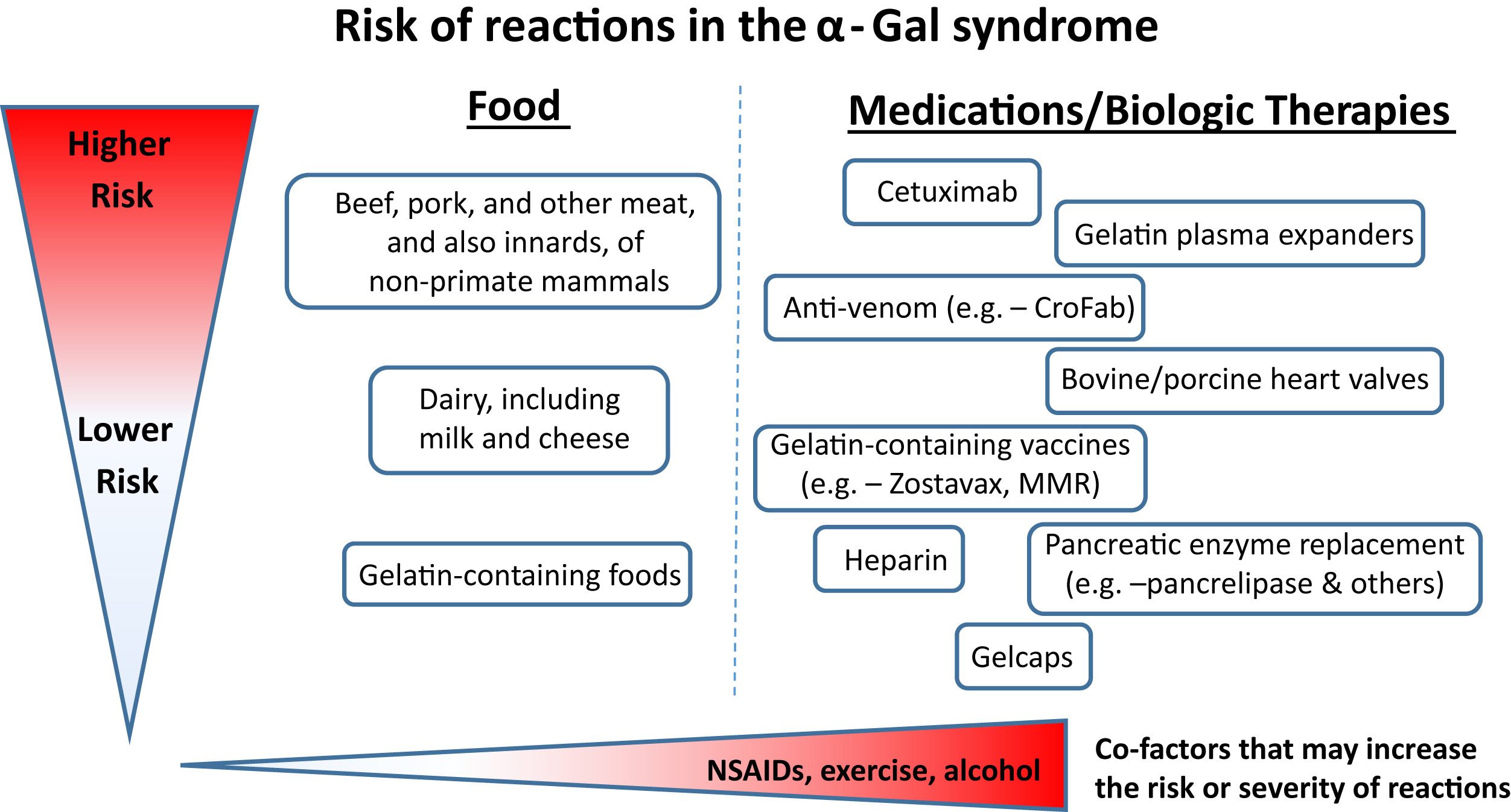

Risk of Reactions

Click on the image below to enlarge

FIGURE 1. The risk and also severity of reactions in the a-Gal syndrome relate to the amount of the oligosaccharide that is present in food, drugs, or other therapeutics. The route of administration is relevant to the speed at which reactions occur; that is, intravenous administration is associated with rapid reactions, whereas oral ingestion has delayed onset. Cofactors such as NSAIDs, exercise, and alcohol can be additional risk modifiers. This schematic reflects clinical experience, as well as challenge studies and laboratory investigations. CroFab, Crotalidae polyvalent immune Fab; MMR, measles, mumps, and rubella; NSAID, Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Reproduced from: Platts-Mills TA, Li RC, Keshavarz B, Smith AR, Wilson JM. Diagnosis and management of patients with the α-Gal syndrome. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 2020 Jan 1;8(1):15-23, with permission from Elsevier.17

Clinical history

In >90% of cases the diagnosis of AGS can be made based on a history of delayed allergic reactions after eating non-primate mammalian meat (e.g., “red meat” such as beef, pork, or lamb) and a positive blood test (>0.1 IU/mL) for IgE to alpha-gal. The combination of both an appropriate clinical history and supporting blood test is necessary to establish an accurate AGS diagnosis.18

Despite growing numbers of clinicians recognizing AGS as a leading cause of adult-onset anaphylaxis, fewer recognize the nonclassical manifestations of this syndrome, resulting in frequent referrals of AGS patients to nonallergy specialists. In an investigation of patients referred to a southeastern US gastroenterology clinic with unexplained GI symptoms consistent with AGS, nearly one-third of patients had positive alpha-gal IgE levels, of which 80% reported symptomatic improvement with mammalian product avoidance.

This case series illustrates the need to consider a diagnosis of AGS in patients with prolonged, nonspecific symptoms such as GI distress, fatigue, arthralgias, and mild cognitive dysfunction following a tick exposure.17,35

As 90% or more of people who test positive for alpha-gal syndrome do not have clinical allergy to alpha-gal, a positive alpha-gal IgE test alone is not sufficient for the diagnosis of alpha-gal syndrome.17,18,19 AGS is diagnosed by a combination of clinical history and testing.17,18

In addition to the usual clinical history collected for diagnosis of food allergy, the following information may be helpful:

- Age of onset (AGS is the most common adult-onset allergy in some high-prevalence areas)3,17,18

- History of allergic reactions to mammalian meat, but note that patients with AGS often react to dairy, gelatin, and other exposures as well.17,18

- Timing of symptoms (AGS reactions typically occur 2-10 hours after consumption of mammalian foods, although not always)1,3,10,17,18

- Atypical allergic symptoms (some people with AGS present with GI symptoms only, joint pain, or other rheumatological symptoms)17,18,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35

- Responsiveness to dietary changes is especially important for diagnosing atypical presentations, like the GI phenotype of AGS17,18

Tick-bite-related information may include:

- History of tick bites, including location and species, if known.17,18,26

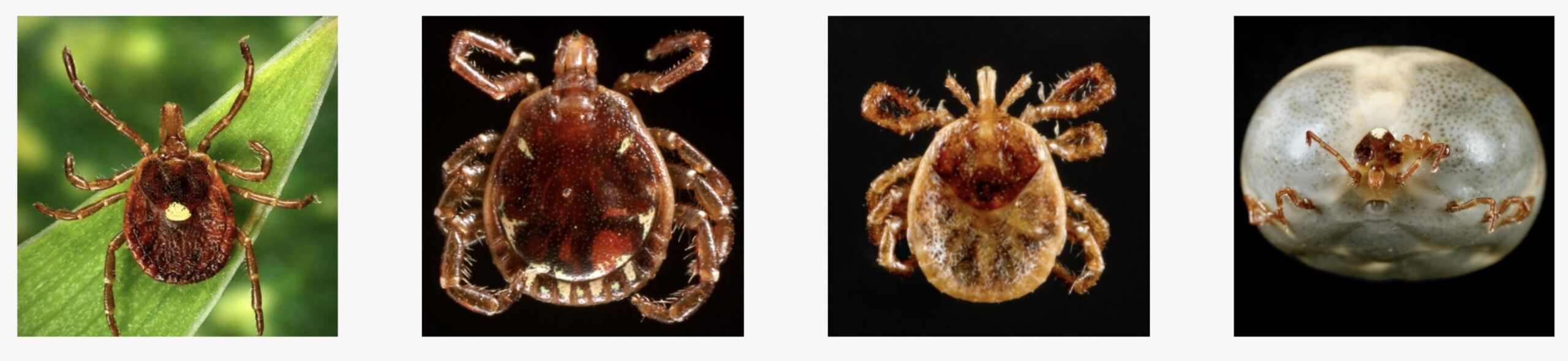

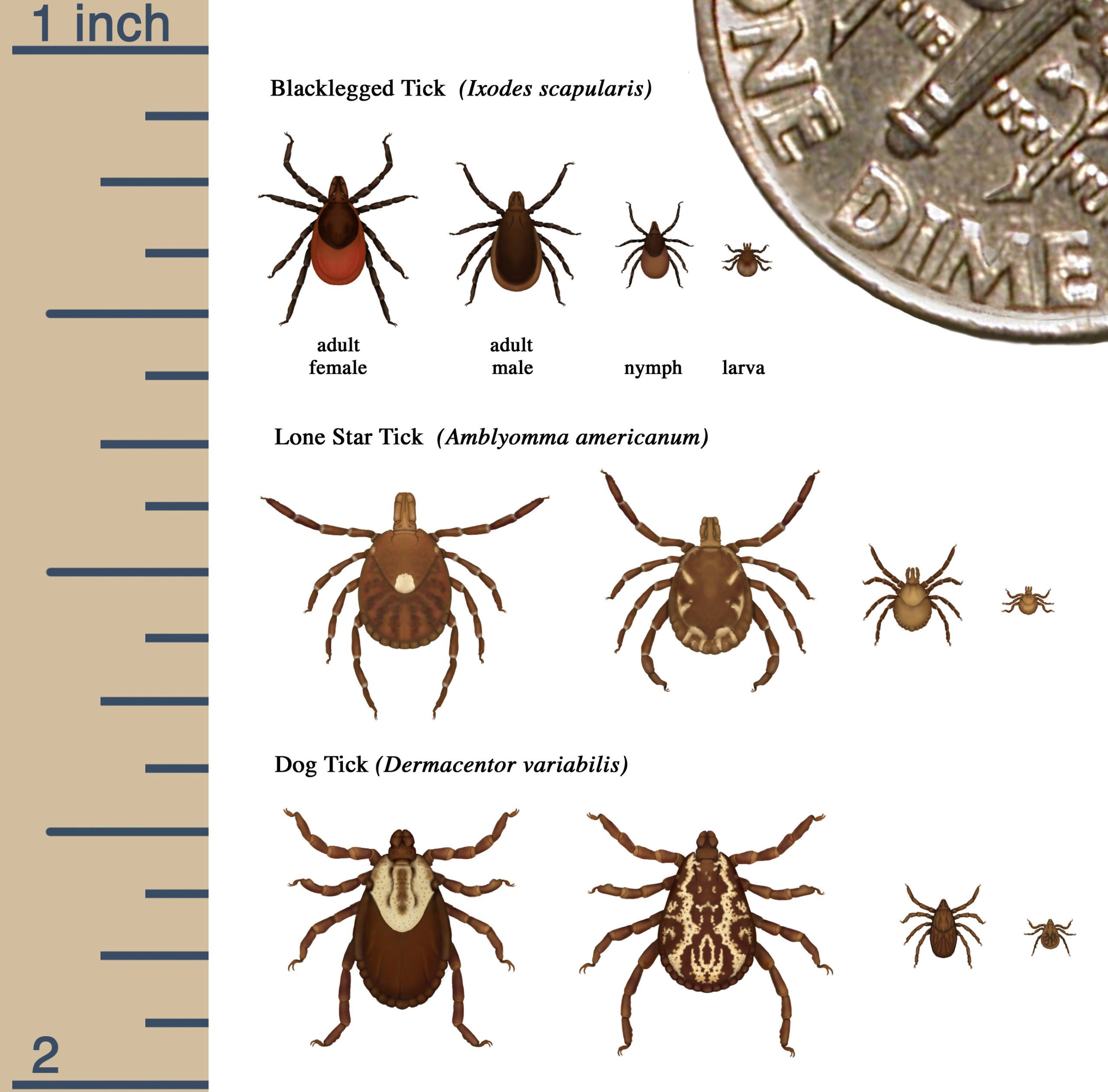

- Many species of ticks around the world are able to induce AGS. In the U.S.:

- AGS is most associated with lone star ticks (Amblyomma americanum).7,17,18

- Preliminary data suggests that, less commonly, black-legged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and Western black-legged ticks (Ixodes pacifica) may also induce AGS.20,21

- The Cayenne Tick (Amblyomma cajennense complex), which is found in south Texas and possibly Florida, and the invasive Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) have been implicated in AGS cases in other parts of the world.22, 23, 24, 25

- Note that all stages of lone star ticks can cause AGS, including larvae. In fact, larval “tick bombs” (clusters of hundreds of larvae) can result in multiple bites, which can increase the likelihood of developing AGS.17,18

- The presence or absence of persistent, localized reactions to tick bites (common in people with AGS)17,18

- History of chigger bites (people often think larval lone star ticks are chiggers)17,18

- History of outdoor activities (data from Lyme disease research suggests that more than half the time, people do not recall tick bites)17,18,36,37

Information about drug reactions:

Alpha-gal IgE

In most cases the diagnosis can be made on a history of delayed allergic reactions to red meat and the blood test for IgE to the oligosaccharide galactose-α−1,3-galactose (α-Gal).17

2025 Labcorp Test Code

650001

Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal), IgE

2025 Quest Test Code

10554

Galactose-alpha-1,3-galactose (alpha-gal) IgE

Total IgE

If the antibodies are ≥2 IU/ml or >2% of the total IgE this makes the diagnosis very likely. We often measure total IgE because some cases are non-atopic and have low total IgE. Recently we saw a case with a convincing history whose total serum IgE was 6.0 IU/ml and sIgE to α-Gal was 0.8 IU/ml. Thus, although the sIgE was < 1.0 IU/mL it was nonetheless > 10% of the total IgE.17

With a convincing clinical history, alpha-gal IgE levels at least 0.1 kU/l confirm the diagnosis of alpha-gal syndrome. With a murky clinical history, some have argued that an alpha-gal IgE at least 2 kU/l or at least 2% of the total IgE should be used to confirm the diagnosis of alpha-gal syndrome.38

Some physicians also order a test for total IgE, as in some cases the ratio of alpha-gal IgE to total IgE is clinically significant, especially in nonatopic patients with low total IgE.17

Additional blood tests

We also check basal serum tryptase levels, as a surrogate for mast cell burden, particularly in those who present with anaphylaxis. Just as anaphylaxis to stinging insect venom can unmask an underlying systemic mastocytosis, individuals with alphagal syndrome have also been subsequently diagnosed with indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM).38

Basal serum tryptase

Basal serum tryptase levels may be measured as a surrogate for mast cell burden.38

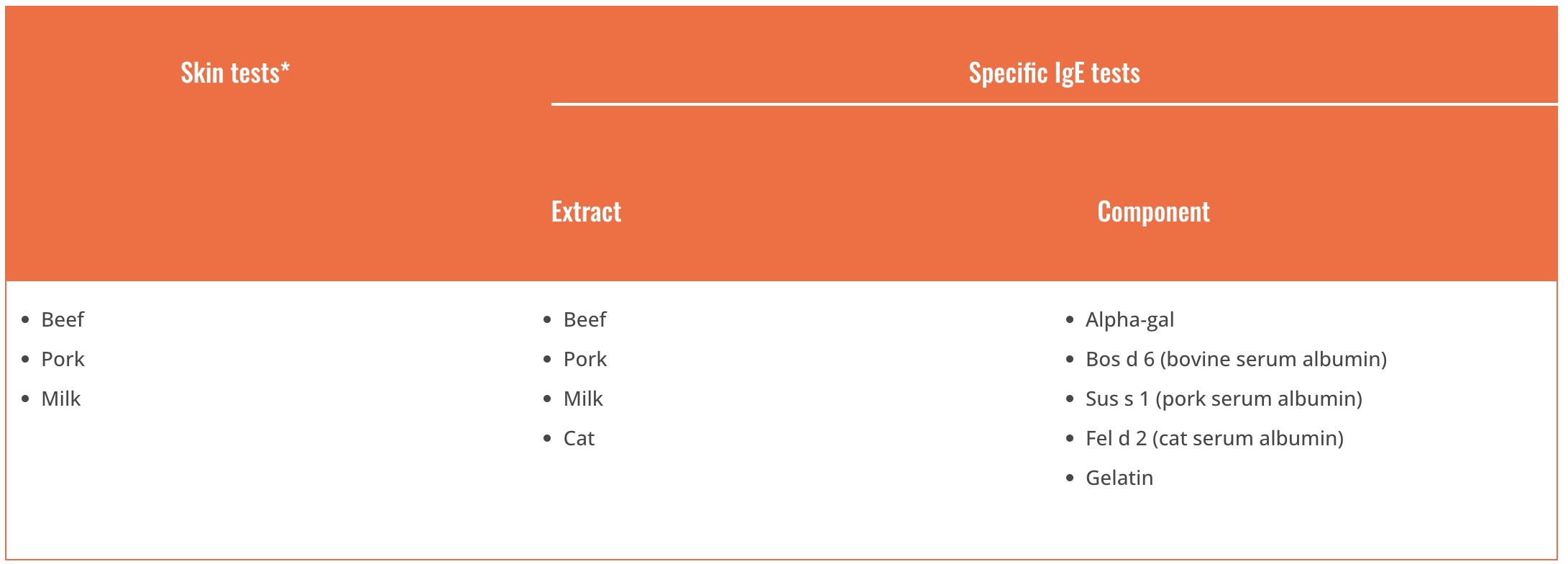

Extract and component tests helpful for ruling out other mammalian meat allergy

In less straightforward cases, additional blood tests may be helpful for ruling out other mammalian meat allergies. See below.17 For more information, see Red Meat Allergy.

Adapted from Wilson JM, Platts-Mills TA. Red meat allergy in children and adults. Current opinion in allergy and clinical immunology. 2019 Jun 1;19(3):229-35.

Less commonly recommended tests

Some test sites include alpha-gal-specific IgE testing within an ‘alpha-gal panel’, which also includes beef, mutton/lamb, pork, and cow’s milk specific IgE testing as patients allergic to alpha-gal frequently have specific IgE that binds to multiple mammal-derived allergens, presumably binding to alpha-gal glycans rather than peptide epitopes. This testing, in conjunction with testing for IgE to cat and dog aeroallergens, serves as a crude surrogate to confirm alpha-gal syndrome if alpha-gal-specific IgE testing is not readily available. However, the alpha-gal-specific IgE and total IgE levels are the most useful serologic tests for confirming the diagnosis of alpha-gal syndrome.38

It appears that the diagnosis of alpha‐gal‐related gelatin sensitisation and allergy may readily be missed by a conventional gelatin sIgE assay. Possibly, the allergenic target for the gelatin immunoassay does not include the alpha‐gal moiety.38

Alpha-gal Panels

Alpha-gal IgE panels include tests for beef, pork, and lamb IgE in addition to alpha-gal IgE. There is alpha-gal in the commercial meat extracts used in these tests. For this reason, beef, pork, and lamb IgE may be positive for patients with AGS.9 However, they aren’t reliably positive. Negative beef, pork, and lamb IgE test results do not rule out the possibility of an alpha-gal-related reaction to these meats.17,18 Meat extract tests are not helpful for determining what foods are safe for patients to consume. Patients with AGS need to avoid mammalian meat even if the meat extract tests are negative (personal communication, Scott Commins, MD, PhD).17,18

Alpha-gal panels are not recommended for diagnosis of straightforward cases of AGS (personal communications, Scott Commins, MD, PhD and Jeffrey Wilson, MD, PhD).

Gelatin IgE

As with beef, pork, and lamb IgE tests, a negative gelatin IgE test result does not rule out the possibility of an alpha-gal-related reaction to gelatin.38

Milk IgE

As with the aforementioned tests, milk IgE test results can lead results to confusion and are not routinely recommended (Scott Commins, MD, PhD personal communication).

The wrong blood test

Unfortunately, sometimes the wrong blood test is performed. The test below is NOT the right test for diagnosing alpha-gal syndrome. It’s for diagnosing Fabry disease.

- Alpha-Galactosidase — NO! this is the wrong test!

- α-Galactosidase A Deficiency— NO! this is the wrong test!

Skin tests

In terms of diagnosis, skin prick tests with extracts of mammalian meats (beef, pork, or lamb) were shown to be unreliable.18

In terms of diagnosis it became clear in early studies that prick tests with extracts of beef or pork were unreliable.18

Skin prick tests

Skin prick tests with commercial extracts of beef or pork are frequently negative or borderline positive. They are unreliable and not recommended for the diagnosis of alpha-gal syndrome.17,18,38, 40

Prick-to-prick tests

Prick-to-prick (prick-prick) skin testing using raw or cooked meats/organs is also used in some cases.18,41,42,43 Please see Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients for more information about this method.

Intradermal skin tests

Intradermal (ID) testing with meat extracts or gelatin-derived medical products is sometimes used in the diagnostic process, especially when blood tests are negative but there is a history of delayed reactions after ingestion of mammalian meat.7,17,18,41 Some studies suggest ID testing with gelatin is more reliable than ID testing with meat extracts.18 However, intradermal testing involves risks, and few clinics perform these tests.18

Food challenges

We have performed over 150 food challenges, which includes those performed for research, for ‘diagnosis,’ and for assessment of clinical resolution. Due to the unpredictable nature of alpha-gal food challenges, risks and benefits should be discussed with patients. This point should not be minimized: in our experience, 15-20% of food challenge reactions in patients with AGS require one or more doses of epinephrine and/or emergency medical transport. Three colleagues have independently contacted us about a severe alpha-gal food challenge reaction in their offices. As a result, we typically use an informed consent process for these challenges.18

Food challenges are used in the diagnosis of AGS less commonly than with other food allergies. They need to be conducted cautiously because of the delayed and unpredictable nature and severity of allergic reactions to alpha-gal.

Commins reports that 15-20% of food challenge reactions in patients with AGS require one or more doses of epinephrine and/or emergency medical transport.18

In Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients, Commins describes the instances in which alpha-gal food challenges are clinically appropriate and makes recommendations as to how to conduct them.

1. Patient with unclear etiology of possible allergic episode(s) and has positive alpha-gal IgE >0.1 IU/mL but reports ongoing, asymptomatic consumption of beef, pork, etc

2. Patient with known history of tick bites (or significant tick exposure) who tests positive for alpha-gal IgE >0.1 IU/mL and was told to avoid red meat due to the test result without supporting symptoms

3. Patient with alpha-gal IgE <2.0 IU/mL who fully tolerates high fat cow’s milk dairy ice cream, is able to consume a single slice of pepperoni (~12 g) without symptoms and reports no tick bites in the past 12 months

4. Patient with history of AGS, followed longitudinally, who now tests undetectable (e.g., <0.1 IU/mL) for alpha-gal IgE

5. Patient has a history suggestive of AGS but tests negative (<0.1 IU/mL) for alpha-gal IgE and diagnostic clarification testing discussed above has been unrevealing [food challenge has been positive in 7 of 11 patients in this scenario].18

Seronegative AGS

Approximately 2% of patients with AGS test negative for alpha-gal IgE.27 Commins describes a multi-step protocol used by a referral center for diagnosing patients with a history of reactions to mammalian products who test negative for alpha-gal IgE.18 This is detailed in Diagnosis & management of alpha-gal syndrome: lessons from 2,500 patients and can include:

- The assessment of surrogate markers (beef, pork, lamb) by skin and serum IgE testing18

- Testing for cat serum albumin (Fel d2) to identify patients with pork-cat syndrome18

- Testing for IgE to both porcine and bovine gelatin18

- Skin testing using alpha-gal-containing biologics such as cetuximab18

- Basophil activation testing18,44

This approach has led to diagnostic clarification in 78% of patients with seronegative testing who report compelling symptoms.18